For the first time, welcome to the Paradaida blog! I’m Adam Kavanagh, your resident butterfly brain, and today I’m going to be talking about Biodiversity Net Gain, an environmental policy initiated in February 2024 by the British government. Does it help or hinder the efforts of many to combat the advanced recession of biodiverse life? It can probably be gleaned from the title how this topic fares under the microscope, but if environmental governance is going to be effective on the local and national level, then honest discussion is needed around these policies and their adjoining sciences too. I hope that I provide you with a better understanding of the topic at hand, and feel free to join in and leave a comment for me at the bottom of the article.

Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG): Beginnings

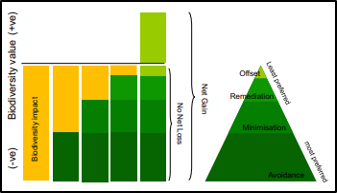

The question of how urban infrastructure can be created and managed to the benefit of the natural world has a great deal of value stacked behind it, ever increasing the further on we go as a species into the climactic unknown. For much of the 20th Century humanity has strived to understand natural systems, their necessity for a productive world and our negative impacts on them. There have been marked successes, from the enthusiastic uptake of renewable technologies, the creation and maintenance of large environmental regulation frameworks (Train 1996), and the restriction of DDT and organochlorines from widespread proliferation (Bonneuil 2015) to name but a few. But there have also been alarming failures, like the proliferation of PFAS ‘forever’ chemicals in waterways across Europe and Asia, efforts to halt deforestation that consistently come up short and our currently unfolding horror at the ubiquity of microplastics. It is under this spotlight braided with the light of opposite outcomes that the UK and BNG rise to the arena. Through a blending of governmental policy, financial strategy and science the biodiversity mitigation strategy was born (shown at its most basic in Fig. 1), with biodiversity offsetting (BO) being the final step in this mitigation process. To date there have been over 3000 offsetting projects covering >153670km2 (Simpson et al. 2021), showing this conservation technique to be globally accepted in governmental policy even when environmental science is yet to catch up (Gelcich et al. 2016), and it is this specifically that we will be focusing our gaze on.

Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG), a flagship policy of the Environment Act 2021 in Great Britain, is based on the concept of BO (which itself is a form of ecological compensation). BO involves replacing and maintaining habitats to offset the destruction or amendment of habitats or ecosystem services due to human development (Bull et al. 2013). While the basis of this can differ and the UK also requires that the mitigation process above be engaged with, it has been mandated since February 2024 that new developments comply to a BNG of at least 10% (DEFRA 2024) using Ecological Impact Assessments (EcIA) and an Excel-based biodiversity calculator tool. This tool takes into consideration multiple factors (distinctiveness, condition, project failure risk, landscape-scale importance) to create baseline biodiversity units and compare them to biodiversity units that are proposed/predicted by the developer (zu Ermgassen et al. 2021). This is intended to reinforce the existing mitigation mechanisms that exist for natural protection, and if developers plans or predictions are found to be inadequate, they will be made to amend them (Natural England 2022). This offsetting can take the form of the upgrading of existing habitats or creation of the same habitat elsewhere (like-for-like offsetting (Quétier and Lavorel 2011)) or the trading of one habitat for another functionally different habitat (out-of-kind offsetting (Bull and Brownlie 2017)). As of 2019 there were more than 100 countries that had signed BO legislature into law, representing a doubling in the last 20 years (Kujala et al. 2022).

Is The Concept Underpinning BNG Scientifically Sound?

For the success of any scientific concept, topic or discipline, guidelines must be drawn up, definitions agreed upon, standards created etc. However, the differences in definitions and standards found in BO is a cause for concern. In a review of the current literature on BO, Mcvittie and Faccioli (2020) found that no consensus had been found for how to measure the losses and gains from biodiversity offsetting (Maseyk et al. 2020), and no agreement has been reached on how mandatory “proof” of said losses and gains is. Furthermore, core components of BO are still being deliberated upon (McKenney and Kiesecker 2010), such as equivalence (in-kind vs. out-of-kind), site locations (on-site vs. off-site) and additionality (Laitila et al. 2014), while the benefits of landscape-level mitigation over property-level mitigation in conservation are also debated (Kennedy et al. 2016) with implications for offsetting in this current methodology. Finally, Taherzadeh and Howley (2017) found that defining no net loss was difficult even when interviewing stakeholders in the conservation industry, and that the types of compensation attainable was under-investigated.

Some voices in conservation take issue with BO on wider grounds. Both Simmonds et al. (2019) and Damiens et al. (2021) opine that creating this framework entrenches ongoing biodiversity loss in the construction industry and the social consciousness. This point is shared by Maron et al. (2012), suggesting that this could confer incentives that act as a safety net to developers instead of fostering understanding/care for the landscape that is being developed. The authors found 3 major barriers to effective offset restoration: poor measurability, long time lags, and uncertainty. Gordon et al. (2015) reveals 4 incentives likely to reverse any possible good done by such policies: entrenching and worsening of baseline declines, the ability to wind back other conservation efforts behind “compliance”, the privatisation could crowd out/alienate volunteer communities, and false confidence in the success of the offsets given. Walker (2009) found that even if “no net loss” could be achieved political dealings, human interest and sheer complexity would make BO administratively improbable, while Gibbons et al. (2015) developed a calculator to predict the feasibility of “no net loss”, showing it was only feasible if the offsets were secured in advance. BO has yet to translate to any success for forested landscapes either and its suitability for much of the UK could be diminished due to our primary habitat types (zu Ermgassen et al. 2019). There also appears to be a conflation in the industry between no net loss and net gain in terms of methods and processes necessary to achieve either of these ideals as Bull and Brownlie (2017) elucidate, and this dislike of oversimplification is understandable. Finally Curran et al. (2014) go further, charging restoration offset policies with creating a net loss in biodiversity, performing analyses on 108 studies of passively recovering and actively restored habitat. The results show the time lag for these projects to achieve no net loss could be decades or possibly centuries (mostly due to slow recovery of assemblage structure), with an 82% failure rate for offset projects (supported by Suding (2011) finding a success rate of 30%).

The Marriage of Two Industries: Opportunities Created by BNG

Whether it can be agreed upon or not that the commodification of nature is allowable or even fully possible (Smessaert et al. 2020), BO and BNG has found a way to economise natural frameworks, and therefore bring to the fore its attractiveness to urban developers (though there are still many issues between the two groups (Sullivan and Hannis 2015). BNG itself may represent the equivalent of a level playing field for all companies private or public, and clear governmental policy will only strengthen this (Hoskin 2019) through the standardisation of legal definitions for planning and transparency of procedures that avoids any extraneous cost to the developers (DEFRA 2013). These economics allow this to be integrated with the concept of carbon credits, potentially creating an industry for biodiversity credits to be sold in (The Biodiversity Consultancy 2016). The provision in the law that allows developers to replace lost biodiversity with offsite gains may help to deal with the severe fragmentation of habitat present in England, with knock-on effects expected for regional and local biodiversity (Synes et al. 2020, Fletcher et al. 2018). Lastly it cannot be understated how important the extra financial capital is to the conservation industry, which finds itself in desperate need of funding and fresh ideas to make more conservation projects operational (Simpson et al. 2021).

How Effective is BNG In Its Implementation?

As can be surmised by the preceding content of this review, the literature on BNG and its surrounding mechanisms is patchy, and what can be found paints an unfortunate picture. Firstly, the financial situations of environmental organisations must be touched upon. Natural England have had their budget slashed in the 8 years between 2010 and 2018 from £242 million to £100 million (Harvey 2019), while local councils faced with consistent funding cuts want to sell council assets (57%) and more than 50% have been forced to use financial reserves. This pressure has created a 39% decrease in planning function of expenditure and a 15% loss in staffing (LGiU and TMJ 2019). This raises major issues in the necessary monitoring and regulation of such developments and ensuring that future gains are delivered in reasonable time (Knight-Lenihan 2020).

When studying BNG policy in action, the situation is much the same. Studying the planning applications of 6 local councils with BNG policies in place from 2020-2021, zu Ermgassen et al. (2021) found a 34% reduction in green space with a promised increase of biodiversity units (BU) of 20.5%. This promised increase comes from ‘trading up’ large areas of low BU for smaller highly biodiverse areas, but evidence of this remains to be seen. This in essence confirms Maron et al. (2012) in recognising uncertainty as a major barrier. In addition, as it currently stands national infrastructure projects are exempt from BNG, which cannot be understood considering the context and possible scale of these projects individually (NIC 2021). Fundamental issues are at play here, with Drayson and Thompson (2013) finding that EcIA’s, while highly implemented, tended to be low quality. Embarrassingly this is a follow-up to a 1997 review (DETR 1997) that also found low quality in ECIA’s being produced at the time.

Backing up findings by Gibbons et al. (2015) mentioned in the previous section, Hawkins et al. (2023) found that to achieve no net loss, offsets were required to already be in place for irreversible adverse losses not to be created, while also mentioning that offsetting does not work for food production unless met with a societal dietary change, as any offset area involving farmland would still need to be found somewhere else to meet demand. Finally, a report by Carver and Sullivan (2017) studied how equivalence was being proposed/created between affected sites and proposed conservation sites. This highlighted the fact that the metric was being “creatively amended” to meet the needs and conflicts of the development, that equivalence created losses that were unavoidable as habitats were unsuccessfully compared to each other, and that the pressure to give and create value was diminishing conservation yields (further backed up by predictions made by Hannis and Sullivan (2012)).

Future Recommendations

Hawkins et al. (2023) suggests some recommendations on how to strengthen analyses of biodiversity offsetting and its constituent parts. Firstly, the lack of understanding on which habitats are threatened with development and how these are individually affected hampers calculations for costs and conversions, putting out-of-kind offsetting in an awkward scientific position. This is rectified with more research/outreach to stakeholders in the industry. They also mention that much could be improved in development plans if detailed research on habitat suitability was done, and funding for this is suggested. Finally, while it was calculated that 10-13% of funding for BNG could be created by a biodiversity unit market, environmental and governmental organisations must provide other more primary methods of funding, such as the creation of a central nature recovery fund.

Sullivan and Harris (2015) expound the need to find ways to involve offset suppliers, landowners and policy makers in decisions to have positive adoption by the wider industry. This is seconded by Simpson et al. (2021), and the need to revisit existing incentive systems is not only necessary to mitigate possible negative incentives, but to reengage agricultural landowners. This is explored in terms of payment schemes to private landowners by McDonald et al. (2017), with the result of different payment schemes varying wildly, highlighting a need to understand the outcomes of each form of input payment. Also recommended is the adoption of game theory to understand the outcomes of community-based reactions and interventions.

Mcvittie and Faccioli (2021) highlight the need for more suitable ways of measuring specific habitat characteristics (condition, type, locality), recommend the integration of ecosystem services into BNG goals and success factors, and for more technical expertise and more robust approaches than currently used in policy creation. Zu Ermgassen et al. (2021) recommend simply strengthening the mitigation process before BO is reached, thereby using BO as an emergency option when all other mitigation paths have been considered. This is supported by Curran et al. (2014) who found that active restoration was incredibly positive on most ecosystem indicators, but time lag interfered with its effectiveness, a facet of BO that is built into the policy structure of BNG, therefore requiring increased effectiveness of other mitigation efforts.

Outro

To close out, I have to say it looks to be a difficult and windy road where UK environmental policy is concerned. I distinctly remember the at that time Conservative government hot on the TV interview circuit talking about how revolutionary, how absolutely first-grade this governance plan was. The proof is in the pudding as they say but so far, I have yet to see such sweet treats grace my mind. Instead, I am left with holes, lots of them. To drive this point home, a report released just 5 days ago found that in a sample set of 6000 homes, developers had reneged on biodiverse and natural promises given under the auspices of BNG. 75% of bird boxes promised could not be found. 82% of edge seed mixes were missing, along with 48% of the native hedging and 39% of the trees included on planting plans. Invertebrate boxes were non-existent in entirety. This paints an incredibly bleak picture of Biodiversity Net Gain, and not from the science up as I have done here, but from the developer down. There is no point in the engagement with such principles and concepts if the gatekeepers of these industries act in such a dismissive manner, and I hope that in the future repeat studies show that uptake has been exponentially increased. This I believe is a completely necessary first step towards stopping the flow of harm from human to nature, redressing the balance between us and our wilder cousins.

Thanks for visiting, till next time!

Paradaida

References

The Biodiversity Consultancy (2016) ‘Government polices of biodiversity offsets: Briefing note’, The Biodiversity Consultancy. Unpublished. Available at: https://www.thebiodiversityconsultancy.com/fileadmin/uploads/tbc/Documents/Resources/Government-policy-2.pdf

Bonneuil, C. (2015) ‘Tell me where you come from, I will tell you where you are: A genealogy of biodiversity offsetting mechanisms in historical context’, Biol. Cons., 192, pp. 485-491. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.09.022

Bull, JW. et al. (2013) ‘Biodiversity offsets in theory and practice’, Oryx, 47(3), pp. 369-380. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S003060531200172X

Bull, JW. And Brownlie, S. (2017) ‘The transition from no net loss to net gain of biodiversity is far from trivial’, Oryx, 51(1), pp. 53-59. Available at: doi:10.1017/S0030605315000861

Curran, M. et al. (2014) ‘Is there any empirical support for biodiversity offset policy?’, Ecol. App., 24(4), pp. 617-632. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0243.1

Carver, L. and Sullivan, S. (2017) ‘How economic contexts shape calculations of yield in biodiversity offsetting’, Cons. Biol., 31(5), pp. 1053-1065. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12917

Damiens, F. et al. (2021) ‘Governing for “no net loss” of biodiversity over the long term: challenges and pathways forward’, One Earth, 4(1), pp. 60-74. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.12.012.

DEFRA (2013) Biodiversity offsetting in England. Available at: https://consult.defra.gov.uk/biodiversity/biodiversity_offsetting/supporting_documents/20130903Biodiversity%20offsetting%20green%20paper.pdf

DEFRA (2024) Biodiversity Net Gain. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/biodiversity-net-gain

DETR (1997) ‘Mitigation measures in environmental statements’.

Drayson, K. and Thompson, S. (2013) ‘Ecological mitigation measures in English Environmental Impact Assessments’, Journ. Environ. Manag., 119, pp. 103-110. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.12.050

Fletcher, RJ. et al. (2018) ‘Is habitat fragmentation good for biodiversity?’, Biol. Cons., 226, pp. 9-15. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.07.022

Gelcich, S. et al. (2017) ‘Achieving biodiversity benefits with offsets: Research gaps, challenges and needs’, Ambio, 46, pp. 184-189. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0810-9

Gibbons, P. et al. (2015) ‘A loss-gain calculator for biodiversity offsets and the circumstances in which no net loss is feasible’, Conservation Letters, 9(4), pp. 252-259. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12206

Gordon, A. et al. (2015) ‘FORUM: Perverse incentives risk undermining biodiversity offset policies’, Journ. Appl. Ecol., 52(2), pp. 532-537. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12398

Gordon-Jones, J. et al. (2019) ‘Net gain: Seeking better outcomes for local people when mitigating biodiversity loss from development’, One Earth, 1(2), pp. 195-201. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2019.09.007

Harvey, F. (2019) ‘Agency protecting English environment reaches ‘crisis point’’, The Guardian, 29 January. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jan/29/agency-protecting-english-environment-reaches-crisis-point

Hannis, M. and Sullivan, S. (2012) ‘Offsetting nature? Habitat banking and biodiversity offsets in the English Land Use Planning System’, Weymouth: Green House. Available at: https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/6031/1/Offsetting_nature_inner_final.pdf

Hawkins, I. et al. (2023) ‘The potential contribution of revenue from Biodiversity Net Gain offsets toward nature recovery ambitions in Oxfordshire’, Report by the University of Oxford and the Oxfordshire Local Nature Partnership. Available at: https://www.biodiversity.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/BNG-report-final-29-June-2023.pdf

Hoskin, R. (2019) ‘The extraordinary rise and rise of biodiversity net gain’, cieem.net, 19 March. Available at: https://cieem.net/the-extraordinary-rise-and-rise-of-biodiversity-net-gain/

Kennedy, C. et al. (2016) ‘Bigger is better: Improved nature conservation and economic returns from landscape level mitigation’, Sci. Adv., 2(7), e1501021. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501021

Knight-Lenihan, S. (2020) ‘Achieving biodiversity net gain in a neoliberal economy: the case of England’, Ambio, 49(12), pp. 2052-2060. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs13280-020-01337-5

Kujala, H. et al. (2022) ‘Credible biodiversity offsetting needs public national registers to confirm no net loss’, One Earth, 5(6), pp. 650-662. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2022.05.011

Laitila, J. et al. (2014) ‘A method for calculating minimum biodiversity offset multipliers accounting for time discounting, additionality and permanence’, Methods Ecol. Evol., 5, pp.1247-1254. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12287

LGiU and TMJ (2019) State of Local Government Finance Survey 2019. Available at: https://www.lgiu.org.uk/publication/lgiu-mj-state-of-local-government-finance-survey-2019/

Maron, M. et al. (2012) ‘Faustian Bargains? Restoration realities in the context of biodiversity offset policies’, Biol. Cons., 155, pp.141-148. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2012.06.003

Maseyk, F. et al. (2021) ‘Improving averted losses estimates for better biodiversity outcomes from offset exchanges’, Oryx, 55(3), pp. 393-403. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605319000528

McDonald, J. et al. (2017) ‘Improving private land conservation with outcome-based biodiversity payments’, Journ. Appl. Ecol., 55(3), pp. 1476-1485. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13071

McKenney, BA. and Kiesecker, JM. (2010) ‘Policy development for biodiversity offsets: a review of offset frameworks’, Environ. Manag., 45, pp.165-176. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-009-9396-3

McVittie, A. and Faccioli, M (2020) ‘Biodiversity and ecosystem services net gain assessment: a comparison of metrics’, Ecosys. Serv., 44, 101145. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101145

Natural England (2022) Biodiversity Net Gain Brochure. Available at: https://naturalengland.blog.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/183/2022/04/BNG-Brochure_Final_Compressed-002.pdf

National Infrastructure Commission (2021) Natural Capital and Environmental Net Gain. Available at: https://nic.org.uk/studies-reports/natural-capital-environmental-net-gain/#tab-summary

Quetier, F. and Lavorel, S. (2011) ‘Assessing ecological equivalence in biodiversity offsetting schemes: Key issues and solutions’, Biol. Cons., 144, pp. 2991-2999. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.09.002

Smessaert, J. et al. (2020) ‘The commodification of nature, a review in social sciences’, Ecol. Econ., 172, 106624. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106624

Simmonds, JS. et al. (2019) ‘Moving from biodiversity offsets to a target-based approach for ecological compensation’, Conservation Letters, 13(2), e12695. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12695

Simpson, K. et al. (2021) ‘Incentivising biodiversity net gain with an offset market’, Q Open, 1(1), qoab004. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/qopen/qoab004

Suding, K. (2011) ‘Towards an era of restoration in ecology: successes, failures, and opportunities ahead’, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst., 42, pp. 465-487. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145115

Sullivan, S. and Hannis, M. (2015) ‘Nets and frames, losses and gains: Value struggles in engagement with biodiversity offsetting policy in England’, Ecosys. Serv., 15, pp. 162-173. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.01.009

Synes, N. et al. (2020) ‘Prioritising conservation actions for biodiversity: lessening the impact from habitat fragmentation and climate change’, Biol. Cons., 252, 108819. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108819

Train, R. (1996) ‘The environmental record of the Nixon Administration’, Presidential Studies Quarterly, 26(1), pp. 185-196. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27551558

Walker, S. et al. (2009) ‘Why bartering biodiversity fails’, Conservation Letters, 2(4), pp.149-157. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2009.00061.x

Zu Ermgassen, S. et al. (2019) ‘The ecological outcomes of biodiversity offsets under “no net loss” policies: A global review’, Conservation Letters, 12(6), e12664. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12664

zu Ermgassen, S. et al. (2021) ‘Exploring the ecological outcomes of mandatory biodiversity net gain using evidence from early-adopter jurisdictions in England’, Conservation Letters, 14(6), e12820. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.1282